Althea white paper

Updated Althea and Althea L1 whitepaper

Note: This article has been updated to reflect v2 of our whitepaper

Althea

A peer-to-peer routing and machine billing protocol

Althea L1

A micropayment-specialized blockchain network

Whitepaper v2.1 Apr 2024

Justin Kilpatrick, Jehan Tremback, Deborah Simpier, Christian Borst

{justin, jehan, deborah, christian}@althea.net

Abstract

In the seven years since the original Althea whitepaper was published, the Althea networking and billing protocol has been developed and iterated, and it is now used to provide commercial home internet around the world. This updated paper seeks to place the present state of the Althea network protocol in context with new developments. Specifically, Althea L1 as a blockchain platform specifically tuned, but not exclusively for, micropayments generated by routers running the Althea networking and billing protocol.

Althea Protocol Overview

As of January 2024, 5.3 billion people (or 66% of the world) use a device connected to the internet. The ways in which bandwidth is sold, purchased, and consumed have far-reaching implications, making it a topic of significant interest.

The Althea routing and billing protocol (“the Althea Protocol”) allows anyone to install equipment, participate in the decentralized ISP, and receive payment for their service.

This transforms bandwidth from a good that can only be sold in exclusive contracts into a commodity that anyone can purchase dynamically from anyone else. Further, the Althea Protocol is cheaper to use because:

- Nodes dynamically switch between connectivity providers to find a route with the best combination of bandwidth and low cost.

- Overhead costs, like advertising and marketing, are reduced as the only advertisements in this system are the automatic advertisements of price and route quality between nodes. The open-access nature of this system makes it easy for new entrants to participate efficiently.

- Contract and billing costs are eliminated by dynamically routed micropayment, which enables devices to automatically pay each other efficiently.

In this paper, we will unveil the technology that made this achievement possible.

Althea L1 Overview

Althea L1 is a micropayment specialized blockchain network designed to meet the requirements of the Althea Protocol operating at scale. Specifically, it is intended for:

- Fast finality – As soon as a transaction is accepted into the blockchain, it cannot be reverted.

- Low costs to settle payments – Payments on the order of a few cents must be practical.

- Micropayment priority – Payments must be accepted in a predictable manner at all times.

- Efficient light client verification – It must be possible to verify payments quickly with low overhead on embedded devices.

- Integrated EVM – Arbitrary computation offers valuable flexibility in designing supplemental contracts and tokens, allowing for applications that support the micro-payment settlement platform while maintaining its core function.

This unique blend of properties allows the Althea Protocol to achieve scalability, reliability, and longevity—crucial elements for any successful internet service platform.

The full path round trip time extension

Correcting route fraud through metric adjustment

Micropayments versus Payment Channels

the Althea Protocol

Overview

Althea allows routers to meter and pay each other for bandwidth using blockchain micropayments. An important architectural detail is that nodes only pay neighbors for forwarding packets. This allows us to phrase the route price as a routing metric in a distance vector routing protocol such as BGP or Babel (Chapin & Kunzinger, 2006) (Chrobozek & Schinazi, 2021).

On top of this pay-for-forward network, we build a system where consumers can pay for internet access. The Althea Protocol is intended for use in local “mesh” networks (Frangoudis et al., 2011).

Network Overview

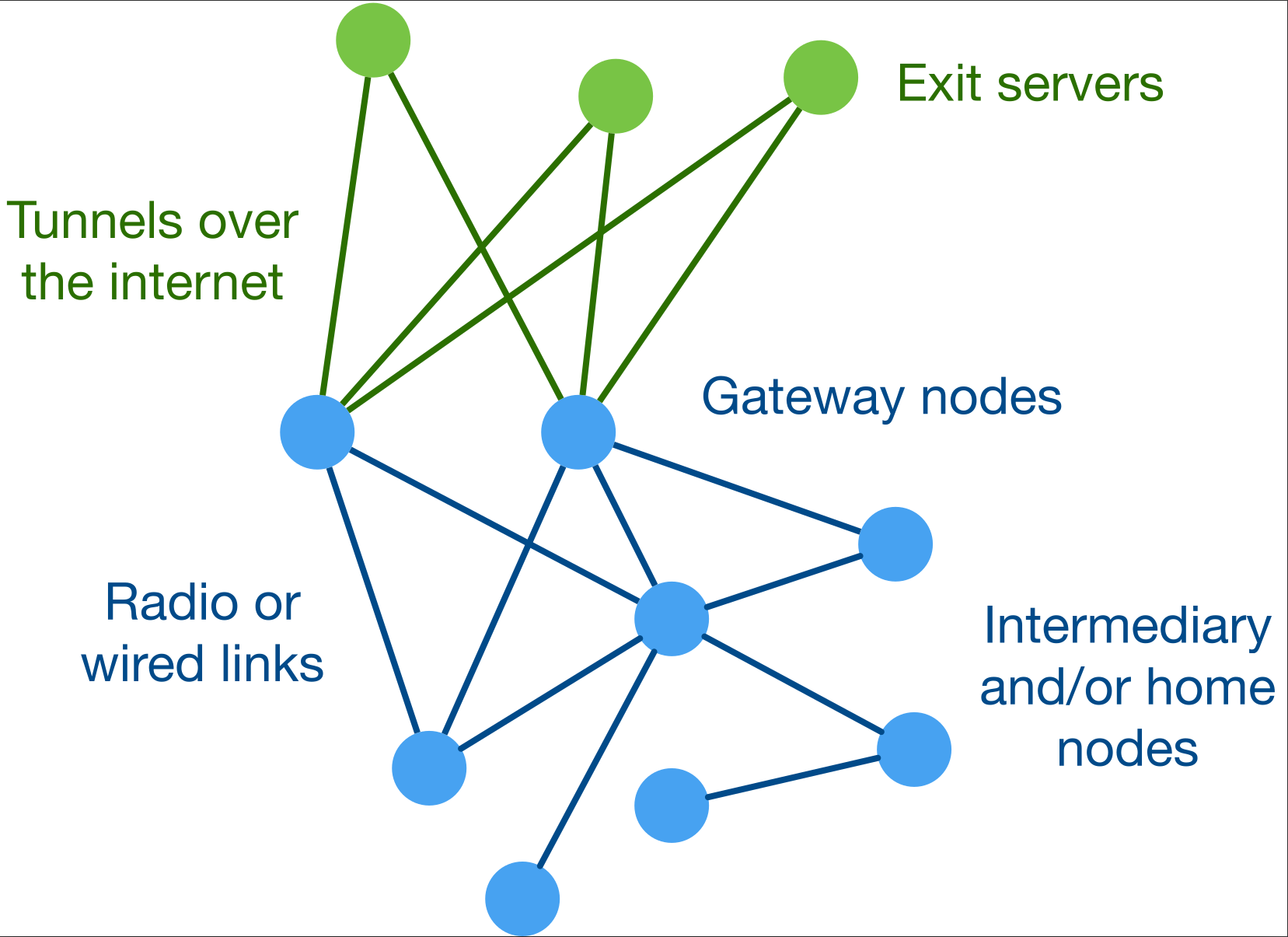

To simplify the explanation of Althea's network architecture, we present several 'roles' that devices may perform. Note that these are logical roles, not physical ones. So, a single device may perform several or even all of these roles simultaneously:

- User nodes are installed by individuals seeking internet access through Althea. These nodes function similarly to traditional ISP-provided routers/modems but with a critical difference: they operate independently of any single ISP. User nodes connect everyday devices to the Althea network, handle payments, and provide standard networking services like WiFi and LAN connections.

- Intermediary nodes are installed by connectivity providers seeking to earn income by forwarding internet traffic. These will often be more powerful and placed strategically with good line of sight to other nodes. Notably, most nodes function as both intermediary and user nodes since the same software allows for buying/selling bandwidth and relaying traffic. A well-placed home router can carry substantial traffic and generate revenue.

- Gateway nodes are specialized intermediary nodes that directly connect the Althea network to the wider internet via low-cost sources like internet exchanges or business-grade connections from a conventional ISP. They bridge Althea's physical network to the outside world, while exit nodes operate the link to the wider internet.

- Exit nodes, potentially hosted in data centers reachable over the internet, are connected to gateway nodes via VPN tunnels. They serve two essential purposes: first, measuring network quality to enable optimal gateway node selection, and second, handling the legal responsibilities of an ISP (like address translation and copyright matters). This frees gateway nodes to focus solely on bandwidth provision without monitoring user traffic.

Read more about the network architecture in the Network section.

Routing Overview

In the Routing section, we define a couple of extensions to the Babel routing protocol. Babel was selected because it has several valuable properties we can use. However, any distance vector routing protocol could be modified to exhibit the properties Althea requires. Distance vector protocols are already used extensively on the internet, with BGP being one of the most well-known ones.

Routing in distance vector protocols is based on an advertised connection quality metric. Nodes send an announcement packet stating their identity and existence to the network once every predetermined period. These announcement packets are then passed from node to node. Each node updates the metric to reflect the connection quality between it and the neighbor where it got the announcement. Using this information, each node can build up a routing table of the best neighbors to forward packets to reach any network destination in O(n) time on each node.

We have also added a verifiable quality metric and a price metric to the existing distance vector routing.

A verifiable quality metric is a connection quality metric that can be verified by a node and the destination where it is sending packets. Our first extension to Babel allows nodes to verify the metrics advertised by their neighbors.

To advertise prices, a second metric is added to the routing advertisements, this time containing a ‘price’ value for some arbitrary but agreed-upon amount of data transfer. When passing advertisements, each node updates the price field with its fee for passing data. Routes are then selected by optimizing the quality metric vs. the price metric and paying the selected total sum required to route all the way to the destination.

These two extended metrics have the net effect of ‘unbundling’ the traditional metric field in Babel, a simple unsigned sixteen-bit integer each router adds to based on their own determinations of packet loss and optionally latency. This enables independent decision-making across the network, transparent pricing, and objective quality validation.

Payments Overview

Each node on the network establishes an internal account for each of its neighbors. Bandwidth is then tracked as described in the Metering section and used by each node to independently compute what it is owed and what it owes each neighbor.

A network-wide threshold is set at which payment is expected. For example each node would expect to be paid after a specific monetary value of bandwidth was used. Example values could include 1c or 50c, but all network nodes must agree on this value.

If a payment is expected but not delivered at any given time, the unpaid node will throttle or entirely cut off connectivity.

Micropayments create a low-risk environment for both buyers and sellers. For buyers, the risk is minimal: they might prepay a neighbor node for bandwidth that becomes unavailable. Likewise, sellers might provide bandwidth to a node unable to pay, potentially missing out on other customers. However, the small payment amounts keep potential losses insignificant for both sides.

Despite using micropayments, trust is still a factor. We have chosen a 'pay after' model to minimize risk. In a 'pay before' system,’ malicious nodes could repeatedly profit by taking payment without providing service. With 'pay after,’ however, those refusing payment gain nothing but a bad connection, making exploitation pointless.

Each node also pays an exit node to forward traffic from the internet to them. This is how ‘download’ traffic is paid for in a pay-for-forward network. Read more about exit nodes in the Network section.

For the purposes of the Althea Protocol, any unit of account can be used for payments. Potentially, multiple currencies could even be used within the same network simultaneously. Nevertheless, in general, stablecoins will be used and agreed upon as the payment currency by a network running the Althea Protocol.

Payments for operators

In traditional ISPs, network management (like handling support calls, performing new user installations, and troubleshooting issues) is typically bundled together with the use of bandwidth and hardware access.

While network management is not technically part of the Althea Protocol, it is a problem we must consider to make a distributed ISP possible and practical for everyone.

The base Althea Protocol software can be extended with third-party management tools, allowing for the same maintenance and troubleshooting possible in a traditional ISP.

“Network operators” are businesses that support the Althea Protocol nodes on behalf of the end-users and are compensated based on an agreement between the customer and the operator.

While most telecom companies charge a flat monthly fee, regardless of actual usage, Althea’s system is different. Users pay hourly based on the network operators they choose. This hourly billing ensures that users only pay for what they use while encouraging network operators to keep them connected. Plus, it works seamlessly with Althea's system for micropayments, so users never experience significant, unexpected charges.

Althea's protocol gives users the power to easily switch between network operators. This creates a competitive market where providers are incentivized to provide excellent service, keeping networks reliable and prices fair.

Routing

Routing in Althea is based on the Babel routing protocol (Chrobozek & Schinazi, 2021), a proven distance vector protocol known for its robustness and performance. Babel employs a distributed version of the Bellman-Ford pathfinding algorithm, where nodes first evaluate link quality to their neighbors (link cost). They then share reachability information, including quality metrics, starting with their immediate neighbors.

When a node learns about a destination, it calculates a 'route metric' – a composite score factoring in the quality advertised by its neighbor and its own link cost to that neighbor. This metric indicates the overall quality of reaching the destination via multiple hops. The neighbor offering the best metric becomes the next hop on the route, and Babel updates the Linux kernel's routing table to direct traffic accordingly.

From the Babel specification:

As with many routing algorithms, Babel computes the costs of links between any two neighboring nodes, abstract values attached to the edges between two nodes. [..]

Given a route between any two nodes, the metric of the route is the sum of the costs of all the edges along the route. The goal of the routing algorithm is to compute, for every source S, the tree of the routes of the lowest metric to S.

In the Babel protocol specification, all link quality measurements are folded into a single metric field. This includes packet loss, round trip time, and manual adjustment factors provided by that node. Aggregating all these different values into a single metric used to make decisions is a key part of why distance vector protocols are efficient.

While a single metric value simplifies route selection, it is impossible for the destination to disaggregate it. When selecting a route, a node cannot know if packet loss or latency contributed to a poor metric. Further, the metric alone does not reveal the bandwidth pricing across the entire path, making optimizing routes based on cost and quality harder.

As discussed in the Routing Overview, our two Babel extensions add verifiable quality and price metrics. These values are stored and transmitted separately from the main ‘metric’ field in protocol messages and are used in route verification and billing.

While the extended Babel protocol now tracks three metrics, routing decisions must be made using only one. Based on user preferences, the metric field is adjusted based on the price and route quality values from the other two metrics. The resulting final metric is used for route decisions and advertising to neighbors.

This solution allows the Althea Protocol to leverage the high efficiency of distance vector protocols while transmitting more decision-making information to each node. Note that a given node cannot select the entire route through the network that traffic will take, only the next hop.

Each node sees the price and latency of a given route and weighs these values individually in its own metric decision. However, that decision impacts other nodes that may have made different decisions given the same information based on their preferences.

Routing algorithms that allow the sender to specify the full path exist, called ‘source routing protocols’. However, the overhead of these routing protocols is dramatically higher. Consider a case where a minor link between two nodes has changed in quality. In a source-routed network, every node must be notified of this change. In a distance vector routed network this change would not trigger any additional overhead since the route was not the optimal one to any destination.

Empirical studies have shown that a Babel network of 4000 nodes produces ~1.8mbps in overhead traffic. Given modern hardware and network link speeds, this is a more than sustainable number and does not account for many potential optimizations.

Route metric verification

Distance vector routing protocols have vulnerabilities (Teli et al., 2022). Although the Althea Protocol does not introduce entirely new attack vectors, it does change the potential incentives, requiring careful consideration.

Participation in a network running the Althea Protocol should be as permissionless as possible, meaning anyone can join and participate without

first having to register or otherwise make themselves known to a centralized party.

This means that

an attacker may join at any time and advertise themselves as a false route to a destination. Naive nodes

will then pass their traffic to the attacker, who will collect payment for providing poor-quality

service.

In the Network section, we describe an end-to-end encryption system using exit nodes. Our primary concern is financially motivated attacks where the attacker modifies the routing metrics to attract undeserved traffic.

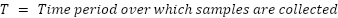

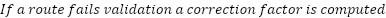

The full path round trip time extension

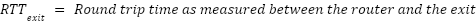

We have implemented a ‘full path round trip time’ extension for Babeld. This is built upon the existing ‘delay-based metric extension’ that tracks latency between individual nodes (Jonglez & Chroboczek, 2024).

Round trip time (RTT) as a metric can be summed along the route or computed purely by the source and destination. This makes RTT a ‘verifiable metric’ that can be used to identify where and when an attacker has lied about the actual quality of a route.

The full path RTT extension calculates the total estimated latency for a route by summing the individual RTTs between neighboring nodes. This information is then included in route advertisements, allowing each node to assess the expected delay to any destination in its local routing table.

Each node has an encrypted connection with an exit node that is used to send traffic from the Althea Protocol network to the larger internet and back. Using this encrypted connection, the client and exit can directly communicate with each other and determine the link’s actual RTT, which can then be compared to the advertised value.

This is sufficient to detect route fraud, and we will describe a simple algorithm to use to do so:

At the time of publishing, only the detection has been implemented and deployed.

In the following sections, we present an algorithm that can correct route fraud if implemented network-wide

by extending this single route validation scheme.

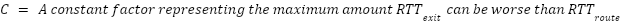

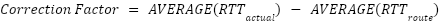

Correcting route fraud through metric adjustment

In order to correct route fraud completely, each node must occasionally perform RTT verification with other random nodes in its routing table. This method is identical to the single-node validation procedure used to detect fraud between a client and an exit node.

The correction factor can then be applied to the

route as advertised by the node performing the validation. For example, a route is advertised as 10

milliseconds in latency and is determined actually to be 30 milliseconds. In that case, the node will

advertise that route as having 30 milliseconds of latency, regardless of the incorrect input.

When applied across an entire network, fraudulent routing will be corrected for and removed over time by eventually isolating corrections to the neighbors of the fraudulent node.

The problem of route fraud is not entirely solvable. The solution presented above could see its effectiveness reduced by half simply by advertising fraudulent routes only half the time. In each round, the attacker would advertise incorrect routes until detected, then stop long enough for new checks to be run and the correction to be removed.

Like the problem of spam email, detecting and mitigating route fraud is an ongoing process that will encourage the development of private algorithms resistant to reverse engineering by attackers.

Despite not being entirely solvable, the problem can be reduced to a simple nuisance with the basic measures described above.

Metering

We have a system for nodes to pay for traffic, but enforcement is crucial. There needs to be some control over which neighbors receive internet access. Anyone could spoof a MAC address and gain unauthorized access, so we need a cryptographic authentication that works for both wired and wireless links.

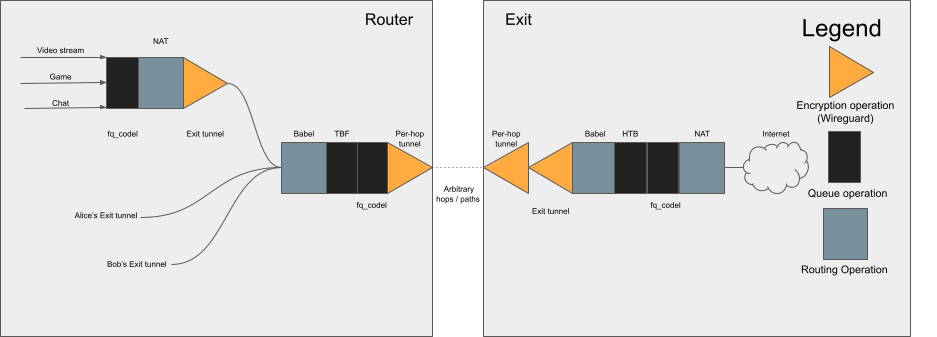

For now, the best approach is using encrypted and authenticated tunneling software like Wireguard (Donenfeld, 2024). A minor optimization would include authentication information in an IPv6 header extension instead of encapsulating in tunnel packets with Wireguard. However, Wireguard is already optimized, and its simplicity makes it the preferred choice for authentication between neighbors and client-to-exit traffic.

Each node negotiates and creates a neighbor tunnel with each of its neighbors. This provides security against spoofing, even in situations like an open wireless network or a shared L2.

In order to correctly compute how much each node owes or is owed by its neighbor, we must do more than simply track traffic on each tunnel. We must also know the destination since each destination has different costs.

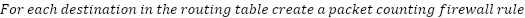

The metering algorithm can be described as follows:

.

.

Nodes must track incoming and outgoing traffic for each destination. This allows them to calculate what they owe to neighbors and what neighbors owe them.

A critical insight is how packet loss affects this system. For example, node A looks at its tx counter to determine how much to pay, and node B looks at its rx counter to determine how much it expects to be paid. Packet loss means that tx >= rx; therefore, B may see more payment than expected.

Since nodes do not react negatively to being slightly overpaid, packet loss does not break the network-wide consensus about how much nodes owe each other.

This is another key property of pay-for-forward, as nodes running the Althea Protocol cannot prove to the outside world how much they owe or are owed. However, they can observe the traffic they have forwarded and authenticated with absolute certainty and independently verify how much they should pay or be paid.

Nodes do not need to communicate with each other about how much should be paid; they simply send payments. Applied recursively, this allows for correct computation of billing data across large and complex networks, essentially applying the Bellman-Ford algorithm to an accounting problem and leveraging its distributed efficiency to practically compute billing data.

Network

The base primitive that Althea is built on is a pay-for-forward network. If all the mechanisms in the preceding sections work correctly, we have a network where nodes can pay each other on a granular level for their service (like forwarding data and verifying that the forwarding is happening correctly). This section describes how Althea provides one of the most popular network services: internet access.

For a network to provide internet access, there must be at least one node, the gateway node, with a connection to the internet (hopefully, there will be many). A gateway node connects to an exit node over a tunnel, which creates a virtual interface that Babel is run on, treating it like any other link.

The gateway node/exit node topology is used by WLAN Slovenija, PeoplesOpen.net, and other community mesh networks (SudoRoom, 2024).

Exit nodes can also be directly connected to a network running the Althea Protocol. However, the gateway node abstraction is useful and frequently used to aggregate traffic or reduce logistics burdens around managing access to the wider internet.

Babel routes to destinations over tunnel connections just as well as over real connections. This means that the nodes do not have to do any explicit gateway selection. Gateway nodes set a price and receive payment for routes to the exit node, just like any other route. User nodes are connected to chosen exit nodes over encrypted tunnels and receive internet access over these tunnels. The only thing that gateway and intermediary nodes see is encrypted traffic between user nodes and exit nodes.

Exit nodes

Exit nodes act as a bridge between Althea’s open, trustless network and the wider internet. They handle the functions ISPs typically manage, except for physical packet transmission. This allows the other nodes to focus only on connectivity, while exit nodes provide customer interface, business, and legal aspects. Althea's model creates a streamlined ecosystem: those skilled in network infrastructure focus on building it, while exit nodes take care of the rest.

Further, exit nodes:

- Deal with public IP addresses – Exit nodes have public IP addresses for user nodes to connect to the internet. They manage NAT functionality for IPv4 traffic and can assign an IPv6 subnet as needed. Distributing an exit into smaller nodes has been the preferred strategy, compared to implementing CGNAT or other methods to use more than one IPv4 address per exit node. Nevertheless, there are no technical limitations that prevent an exit node from implementing CGNAT and serving thousands of users out of a single powerful server.

- Provide encrypted tunnels – All user traffic is encrypted and tunneled to the exit node. This protects privacy and ensures that only the exit node can view unencrypted data.

- Verify routes – Our extensions to Babel allow nodes to verify routes between themselves and a destination. Exit nodes are the destination for a user node’s outbound traffic, and the user nodes are destinations for the return traffic. User and exit nodes work together to keep the nodes on the Althea network between them accurate. User nodes are implicitly trusting exit nodes to perform route verification accurately.

- Deal with legal considerations – Exit nodes act as intermediaries for any legal responsibilities related to internet connectivity. Exit nodes gather data from their users on signup and send the users traffic to the outside world. This protects other nodes, like gateway and intermediary nodes, to only see encrypted packets and allows them to focus on providing connectivity.

- Pay for return traffic – User nodes pay their neighbors to forward traffic to the exit node they are using and onto the internet, but someone needs to pay for the traffic coming back. User nodes give exit nodes some money, which the exit nodes use to pay their neighbors for the return traffic.

Althea L1

The Althea L1 combines many lessons learned from blockchain design over the last decade with the specific needs of the Althea Networking and billing protocol (‘the Althea Protocol’).

Althea L1 is built on CosmosSDK using the CometBFT consensus protocol (Informal Systems, 2024). This is not the highest-performance blockchain design regarding transaction throughput, but CosmosSDK provides the best mix of properties for the Althea Protocol.

Validating and staking

Validators stake tokens in order to produce blocks for the Althea L1 blockchain. Althea L1 uses a Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS) model, meaning that users can delegate their tokens to any given validator and receive rewards minus some amount of commission set by the validator.

Validators and anyone who delegates tokens to them risk losing some of their stake if the validator misbehaves, called slashing. Misbehavior includes failing to participate in block validation or trying to sign multiple versions of the same block.

The rewards for validators and delegators come from inflation and fees. Newly minted ALTHEA tokens are produced at a rate decided by chain governance and transaction fees. Transaction fees are split between the validator who built the block and all validators pro-rata their stake based on the block proposer reward parameter, which is also set by governance.

While it is possible for an unlimited number of validators to join the validator set, only the top N validators will be active, where N is a number selected by governance concerning the tradeoff between faster finality (smaller validator set) and more chain robustness (larger validator set).

Governance

Althea L1 empowers community members to shape the blockchain directly. Anyone can submit a governance proposal at any time by depositing ALTHEA. These proposals have the power to:

- Adjust key parameters: Change things like inflation rates or validator limits.

- Schedule updates: Coordinate upgrades (hardforks) to the blockchain.

- Even change the rules: Modify how much ALTHEA is needed for future proposals.

Only staked or delegated tokens can be used to vote on governance proposals, and a proposal must reach a configurable quorum (usually 1/3 of all staked tokens). Once a quorum is reached, the proposal will pass or fail based on the pro-rata votes of staked tokens.

Each delegator may vote on a proposal based on the weight of their staked tokens. If a delegator does not vote, the validator they are delegating to votes for them. This helps ensure that a reasonable quorum can be met for every proposal.

This functionality provides a decentralized way to make community decisions and change chain parameters by providing transparency to what would otherwise be soft social consensus.

Transaction throughput

Depending on the payment threshold described in Payments Overview, we can estimate roughly how many transactions per hour a home router running the Althea Protocol might need.

The average American household uses around 600GB of monthly data (Layton, 2023). At this speed,

that amount of bandwidth would be consumed in 1 hour and 20 minutes. Assuming 100 million households are

using bandwidth simultaneously at that same speed, we would require a transaction throughput of 2.9 million

transactions per second.

The fastest modern blockchains can support a few tens of thousands of

transactions per second. This example was selected to demonstrate why transaction throughput is not a key property for Althea L1. Instead, we work

on optimizing the number of transactions.

In the above example, two nodes running the Althea Protocol exchange $31 worth of bandwidth an hour. This is an intentionally extreme case. Nevertheless, negotiating a payment threshold higher than 30c is a simple optimization. When routing over a well-known neighbor, the payment threshold, and thus the trust threshold, can be increased without significant risk to the user.

Further, nodes that need to maintain this throughput for long periods and cannot increase the payment threshold can use a payment channel. See the Appendix Micropayments versus Payment Channels. By using a payment channel, unlimited transactions can occur off-chain and only require two transactions on-chain.

Because of the pay-for-forward nature of the Althea Protocol, it is easy to reduce the frequency at which transactions must be committed to the chain. Since each node owes only its neighbor and the exit node for forwarding traffic, it is simple to roll up how much is owed into a single transaction between the two parties.

If nodes target a payment frequency of once every 6 hours and we apply that to our 100 million

node example, the required number of transactions becomes an achievable 4,500 transactions per

second.

We have now presented two strategies for reducing the number of transactions required by

the Althea Protocol:

- Set a target number of transactions per unit of time and adjust the payment threshold to match, or

- Use payment channels to maintain low payment thresholds without creating additional transaction load.

By applying these two strategies simultaneously, it is straightforward to fit a given amount of the Althea Protocol users within an available amount of transaction capacity provided by Althea L1.

Lastly, using Cosmos’ Interchain Security (ICS), it is possible for multiple instances of Althea L1 to operate in parallel, sharing the same validator set (Interchain Foundation, 2024).

Single slot finality

Single slot finality refers to a blockchain consensus mechanism in which all blocks are final as soon as they are produced (Ethereum Foundation, 2024). A block being ‘final’ means that it cannot be reverted during the normal operation of the chain for any reason.

Ethereum’s Proof of Stake (PoS) currently does not have single slot finality. Instead, it takes about 15 minutes for transactions to become final under normal circumstances. During that time, a transaction may be reverted for rare operational reasons.

Any potential delay in finality of a transaction is a severe problem for the Althea Protocol. Bandwidth is being exchanged in real-time, so the Althea Protocol would either have to handle potential transaction reversions or be forced to wait ~15 minutes between payments to allow them to settle.

As discussed in the Transaction throughput section, the ability to adjust payment frequency is a vital part of allowing the Althea Protocol nodes to manage risk. Any delay in finality limits how those options can be used and impose additional complexities on the payment management code required to handle potential reversions properly.

Many users of delayed finality blockchains are accustomed to transactions settling quickly and rarely being reversed. However, for the Althea Protocol to operate at scale, even infrequent reversions could have significant economic consequences. Therefore, the Althea Protocol demands true single slot finality for reliable, scalable operation.

This focus on finality necessitates a smaller validator set, likely under a thousand active nodes. To ensure broader participation, DPOS still enables unlimited stakeholders to delegate their tokens to these active validators, influencing consensus without needing to run nodes themselves.

Light clients

A ‘light client’ is a piece of software that lets you interact with a blockchain without downloading and verifying its full history. This makes it faster and less resource-intensive to use the network.

Light clients can only answer queries about data finalized by the blockchain. If a block has been reverted, a light client could be presented with two valid versions of the same block with no way to distinguish between them. Only by having all the available consensus data is it possible to know which of two versions of the same block is more likely to be valid, at which point the client is no longer ‘light.’

To participate effectively in Althea, users need quick access to accurate blockchain data. Light clients make this possible, even as the network scales. This is true even though it is possible and easier to reduce the number of transactions sent on-chain. To allow the Althea Protocol to operate at scale, sources of information about the state of Althea L1 must be low cost to operate and high-capacity.

Using Merkle proofs, it is possible to prove any piece of Althea L1 state with only a few megabytes of overhead and a few hundred kilobytes per data proved (Interchain Foundation, 2024). A simplified algorithm is described below.

Compact Merkle proofs empower even low-power devices like point-of-sale terminals to

verify Althea L1 state directly. Without this possibility of low overhead light clients, vast server farms

of trusted RPC nodes would be forever required to service device requests, creating a significant barrier to

growth.

Light client capabilities reduce the cost of interacting with Althea L1 for everyone. Even

with an extremely powerful server, verifying the entire history of a chain like Ethereum takes days. With

light clients, initializing a new Althea L1 node and catching up to the present state can be done in

minutes.

Using light client proofs, it is possible to create a ‘hybrid node’ that stores only parts of the state and queries other nodes for any pieces it does not have. By distributing the state across many nodes, each with only partial information, data is made more available, and resource requirements are reduced. It would even be possible for hybrid nodes to act as validators.

Let us use the Cosmos Hub as an example. With 3.7 million accounts, its current state is 14GB (Polkachu, 2014). Extrapolating 100 million accounts would mean around 400GB. This is manageable, and since storage technology typically outpaces blockchain growth, the need for hybrid nodes may be unlikely in the near future.

MicroTx Module

In order to segment and prioritize the Althea Protocol bandwidth payments and other microtransactions from other traffic, a specific module and transaction type have been made.

As discussed in Single slot finality and Transaction throughput, the Althea Protocol requires a significant amount of transaction throughput, and these transactions must be delivered reliably.

By separating the Althea Protocol transactions from other on-chain traffic, Althea L1 can optimize throughput and reliability for this MicroTx transaction type.

For example, if Althea L1 is struggling with transaction demand, the protocol can raise the

minimum size of a MicroTx transaction. This increase effectively obligates the Althea Protocol clients to

increase their payment threshold. In exchange for this increase, Althea L1 avoids becoming overloaded and

continues to include the Althea Protocol transactions in a timely manner.

Likewise, if

there is an excess of EVM transaction throughput that risks overloading Althea L1, the EVM gas fees can be

increased separately. This ensures that MicroTx transactions can

continue to be included without raising the payment threshold.

MicroTx transactions pay a percentage fee in exchange for being exempt from the minimum fee requirements of other transaction types and given priority on inclusion.

While EVM fees can only be paid in ALTHEA tokens, MicroTx fees can be paid in any compatible stablecoin as defined by chain governance.

MicroTx fees are distributed to the validator, including the transaction, and to all validators in a ratio determined by the `base_proposer_reward` governance parameter. This incentivizes validators to include as many MicroTx as possible in each block, which might be detrimental to other types of transactions that do not require highly predictable inclusion.

EVM

Althea L1 has an integrated Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM). The EVM is the most popular and evolved blockchain programming platform by a large margin (Nico, 2024). The goal of including the EVM in Althea L1 is to provide permissionless programmable functionality to help expand the functionality of the Althea Protocol and other similar protocols that may operate on Althea L1.

The primary challenge of the Althea L1 EVM is limiting its use so that it does not provide an undue burden on the validators operating the blockchain. This challenge has manifested in many blockchain architectures, including Ethereum, as the demand for on-chain storage and computation is often highly unpredictable and regularly causes fee spikes, delays, and other disruptions to user transactions.

Due to the design of the EVM, all smart contracts and on-chain storage become part of the chain state forever, with rare exceptions. Unlike chain history, which can be discarded, there is no way to discard parts of EVM state without raising many difficult tradeoffs.

As previously discussed in Light clients, while state growth can be managed, extremely rapid state growth could be fatal to the operation of the chain by making it impractical to run an Althea L1 node.

We are using Ethermint, a CosmosSDK embeddable EVM. By default Ethermint does not implement the fee burning component of EIP-1559. We have modified Ethermint to implement Ethereum’s design of the transaction fee market described in EIP-1559 by having it burn fees (Buterin et al., 2019).

The EIP-1159 design has been augmented so that the Althea Protocol does not remit the priority fee to validators.

The two major outcomes of EIP-1559 implemented in the Althea EVM can be described as follows:

- Fees for EVM transactions are burned, not delivered, to validators and

- A specific gas target is set to encourage predictable state growth.

If gas use exceeds the target, fees increase exponentially until demand returns to

the target level. Likewise, fees decrease if use goes below the gas target.

Althea's EVM burns fees to prevent validators from prioritizing their own profit over the network's primary function. As fees rose, miners accepted private payments to include specific transactions, and they could even game the system by "paying" themselves.

This undermined Ethereum's core economics. Any attempt to adjust gas prices would not reduce blockspace demand since privately negotiated deals bypassed the fee system entirely. This threatened Ethereum's long-term operation.

To prevent these fee markets from disrupting the essential functions of the Althea L1, fee

burning will ensure fees must be paid as specified. It is not anticipated, or intended, that the amount of

ALTHEA burned by this change will be significant to the overall supply compared to typical inflation rates

for DPoS chains.

There is such demand for programmable blockspace because it is extremely useful.

However, the demands of the EVM applications must refrain from interfering with the Althea

Protocol's predictable and reliable function and its overall ability to handle

increased demand without disrupting users.

In the next section, we demonstrate two valuable applications using the Althea L1 EVM.

Liquid Infrastructure

Liquid infrastructure is a form of account abstraction closely integrated with the MicroTx module and links the MicroTx module to the EVM.

A unique problem with the Althea Protocol nodes is that they must make as many micropayments as data is forwarded and, therefore, have some operating balance in each node. Since the private key is active and online in each router, it is possible for a thief to compromise or even physically steal a router (and thus earnings) from bandwidth sales.

Maintaining the secrecy of the private keys associated with Althea nodes or routers can also be challenging for end users and network operators. Network operators must have scripts containing dozens of keys to practically aggregate their earnings from the nodes they operate. These scripts are challenging to secure, making selling or transferring ownership of the Althea Protocol nodes difficult. Since the new owner or operator must either laboriously re-image all the Althea Protocol nodes or simply trust that the previous operator has deleted the private keys.

Liquid infrastructure allows any account on Althea L1 to send a ‘liquify’ transaction for their own account. This transaction creates an ERC-721 compatible contract (an NFT) in the EVM (Ethereum Foundation, 2023). This ‘Liquid Infrastructure NFT’ interacts with MicroTx module payments specifically (Borst, 2024).

Using the `getThresholds` and `setThresholds` endpoints, the user can set a maximum account balance of any specified token. Once this balance has been exceeded, the next MicroTx sending those tokens into the liquified account will migrate excess funds into the EVM and lock them in the Liquid Infrastructure NFT. The Liquid Infrastructure NFT owner can then withdraw these proceeds at any time using the `withdrawBalances` endpoint.

An operator can store unlimited Liquid Infrastructure NFTs in a secure hardware wallet using the same security infrastructure created for Ethereum. Likewise, operators can use the permissionless nature of the Althea L1 EVM to deploy their own contracts to assist in arbitrary management structures.

Using the Liquid Infrastructure NFTs to manage liquified Althea Protocol node accounts, it is much simpler to collect node balances and sell or transfer the nodes by transferring control of the relevant Liquid Infrastructure NFTs.

Exit database smart contract

In addition to the exit nodes architecture, the Exit Node smart contract hosted in the EVM allows for more open management of exits (Hawk Networks INC, 2023).

Our earlier discussion of Exit nodes did not address the problem of key exchange between clients and exits. A simple solution is using a database like Postgres, but this has drawbacks. It requires embedding exit public keys into the Althea Protocol router firmware, adding significant friction to creating a new exit. Many users lack the skill or desire to set up their own exit, forcing them to rely on pre-configured options, limiting choice and decentralization.

Instead, a more practical implementation of the ‘Exit Registration Smart Contract’ contains a list of registered users and a list of registered exits instead of a bespoke instance. In both cases (registry or bespoke instance), a contract administrator validates that a user or exit meets any required criteria before adding their public key information to the database. Devices using the Althea Protocol can then optionally reference the exits list and roam between the provided set of exits. Likewise, a network of exits can take advantage of the open nature of the database to serve many users who would otherwise not select that exit operator directly.

Since blockchain data is public and readable by anyone, using these contracts to receive user public key information can be plug-and-play, unlike exits using a centralized database like Postgres, which must be individually authenticated with the database.

Due to the permissionless nature of the Althea L1 EVM, many exit databases can operate in parallel. Both users and exit operators are free to choose one that best serves their needs.

Native DEX

Althea L1 features a native Decentralized Exchange (DEX) deployed on the EVM to facilitate common token transfers happening on-chain, especially between stablecoins. The Native DEX is a fork of Ambient (formerly CrocSwap) and combines concentrated and constant-product liquidity market maker with many other convenient features.

The Althea L1 Native DEX has been configured to apply governance decisions from Cosmos modules via the `nativedex` module. The `nativedex` module exposes common governance operations as an extension to Cosmos governance, unifying the Althea L1 governance experience across Cosmos and EVM features. Any ratified `nativedex` proposal triggers a function call on the `CrocPolicy` contract, the Ambient governance contract.

`CrocPolicy` features role-based governance control measures with three roles: Treasury, Ops, and Emergency. The Ops role has the lowest authority of all the roles and is restricted to performing common functions to manage pools, like setting fees and configuring the available pool types. The Emergency role can perform all the Ops role functions and enable Safe Mode to disable the DEX in emergencies. The Treasury role can perform all functions and has been connected to the nativedex module to grant Althea L1 governance control over the DEX. By depositing some ALTHEA anyone may propose a change to the native DEX through a governance proposal. The Emergency and Ops roles can be set to multisig wallets by governance and updated at any time through future proposals.

Appendix

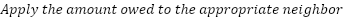

Micropayments versus Payment Channels

In our original paper, we described the use of payment channels. A payment channel is a method for two parties to exchange payments trustlessly by signing transactions that alter the balance of an escrow account held by a bank or blockchain (Hearn, 2013).

While payment channels are a lower overhead way to make efficient micropayments between two parties, they are a poor overall fit for the Althea Protocol.

Payment channels presented challenges in both the implementation and practical application of the Althea Protocol. A device running the Althea Protocol may have an unlimited number of ‘neighbors’ over which it may route traffic. The task of routing is selecting which neighbors will send traffic to the desired destination with the desired cost and quality. Therefore, when both the cost of creating a payment channel and adding or removing funds is trivial, the cost of simply sending a micropayment directly is similarly low, making payment channels an unnecessary complication for practical implementations.

In the case where the cost of creating a payment channel and adding or removing funds is non-trivial, the question of how to optimize what channels to create and how much to fund them becomes central to any implementation of the Althea Protocol. Payment channels only become practical in specific circumstances that do not currently exist in any bank or public blockchain because it is either too costly to manage the channels or too cheap to send payments directly.

This does not mean that payment channels will never be practical, just that they must always be part of a hybrid approach and used to optimize a system that allows for direct micropayments between devices.

If both direct micropayments and channels are available, the optimization problem becomes much more tractable. Devices running the Althea Protocol could negotiate a payment channel only once sufficient payment activity between two parties already occurred to justify the creation of the channel.

References

Borst, C. (2024, February 9). Liquid Infrastructure smart contracts. Github. Retrieved April 13, 2024, from https://github.com/althea-net/liquid-infrastructure-contracts

Buterin, V., Conner, E., Dudley, R., Slipper, M., Norden, I., & Bakhta, A. (2019, April 13). EIP-1559: Fee market change for ETH 1.0 chain. Ethereum Improvement Proposals. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-1559

Chapin, L., & Kunzinger, C. (2006, January). RFC 4271: A Border Gateway Protocol 4 (BGP-4). RFC Editor. Retrieved April 11, 2024, from https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc4271

Chrobozek, J., & Schinazi, D. (2021, January). RFC 8966: The Babel Routing Protocol. RFC Editor. Retrieved April 11, 2024, from https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc8966.html

Cloudflare. (2024, April 10). What is an Internet exchange point? | How do IXPs work? Cloudflare. Retrieved April 10, 2024, from https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/cdn/glossary/internet-exchange-point-ixp/

Dô, C., Kolodziejak, W., & Chroboczek, J. (2021, January). MAC Authentication for the Babel Routing Protocol. IEFT. Retrieved April 11, 2024, from https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc8967

Donenfeld, J. A. (2024, April 12). Wireguard. WireGuard: fast, modern, secure VPN tunnel. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://www.wireguard.com/

Ethereum Foundation. (2023, November 19). ERC-721 Non-Fungible Token Standard. ethereum.org. Retrieved April 13, 2024, from https://ethereum.org/en/developers/docs/standards/tokens/erc-721/

Ethereum Foundation. (2024, February 23). Single slot finality. ethereum.org. Retrieved April 13, 2024, from https://ethereum.org/en/roadmap/single-slot-finality/

FCC. (2021, December 31). Charts - Measuring Fixed Broadband - Eleventh Report. Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved April 10, 2024, from https://www.fcc.gov/reports-research/reports/measuring-broadband-america/measuring-fixed-broadband-eleventh-report

Frangoudis, P. A., Polyzos, G. C., & Kemerlis, V. P. (2011, May). Wireless Community Networks: An Alternative Approach for Nomadic Broadband Network Access. IEEE Communications Magazine.

Hawk Networks INC. (2023, November 28). althea-net/rita: Rita is a routing and billing protocol that allows devices to buy and sell bandwidth. GitHub. Retrieved April 13, 2024, from https://github.com/althea-net/rita

Hearn, M. (2013, June 27). [ANNOUNCE] Micro-payment channels implementation now in bitcoinj. bitcointalk.org. Retrieved April 11, 2024, from https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=244656.0

Informal Systems. (2024, April 12). CometBFT. CometBFT. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://cometbft.com/

Interchain Foundation. (2024, February 12). iavl/docs/proof/proof.md at master · cosmos/iavl. GitHub. Retrieved April 13, 2024, from https://github.com/cosmos/iavl/blob/master/docs/proof/proof.md

Interchain Foundation. (2024, April 12). What is IBC? Developer Portal. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://tutorials.cosmos.network/academy/3-ibc/1-what-is-ibc.html

Jonglez, B., & Chroboczek, J. (2024, January 15). Delay-based Metric Extension for the Babel Routing Protocol. IETF Datatracker. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-ietf-babel-rtt-extension/

Kilpatrick, J. M. (2018, July 9). Babel full path latency and price propagation extension specification. Github. Retrieved April 11, 2024, from https://github.com/althea-net/babel-drafts

Layton, R. (2023, March 23). 2023 Report: Average Home Internet Data Usage Nears 600 GB. Allconnect. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://www.allconnect.com/blog/report-internet-use-over-half-terabyte

Nico. (2024, March 26). Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM). ethereum.org. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://ethereum.org/en/developers/docs/evm

Petrosyan, A. (2024, January 31). Internet and social media users in the world 2024. Statista. Retrieved April 10, 2024, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/

Polkachu. (2024, April 13). Stake with Polkachu on CosmosHub. Polkachu. Retrieved April 13, 2024, from https://polkachu.com/networks/cosmos

Roy, G. (2023, February 16). Ethereum Proof of Stake: Explained. Ledger. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://www.ledger.com/academy/ethereum-proof-of-stake-pos-explained

SudoRoom. (2024, April 12). SudoRoom. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://sudoroom.org/wiki/Mesh/Network_topology

Teli, T. A., Yousuf, R., & Khan, D. A. (2022, February). MANET Routing Protocols, Attacks and Mitigation Techniques: A Review. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 7(2). https://kalaharijournals.com/resources/FebV7_I2_164.pdf